Through his WOB request, Oliver found no fossil fuel ties to Wageningen University. So I thought I would do some research to find out more. Let’s take a closer look at some of WUR’s cosy ties with oil majors such as Shell, BP, Total, and Exxon Mobil, and how WUR enables greenwashing by these companies.

Fossil fuel companies play an overwhelming role in the climate crisis and exacerbate or are complicit in human rights abuses where they operate, from the Niger Delta to West Papua.

They have long known about the impacts of their exploitations of the environment and people. Although some fossil fuel companies have presented climate plans, their actual internal projections do not stack up with the public image.

Most of the Big Oil companies plan to increase oil and gas extraction in the coming decades. But, to remain within 1.5ºC warming, we need a global decrease of 6% in fossil fuel burning per year between 2020 and 2030.

Some people argue that it is good that WUR works with these multinationals since they have the most power to change things, and that these giants are not going away so we must work on changing them from the inside. But there is a major flaw in this argument.

The term ‘greenwashing’ describes how these companies present a sustainable public front (often through disinformation) and bolster their social licence and public image, even in a world that can no longer ignore the climate crisis.

Greenwashing presents these fossil fuel companies as necessary and even beneficial to solving the ecological crises.

One way to boost their reputation is through collaborating with universities, such as by working on sustainable projects at WUR.

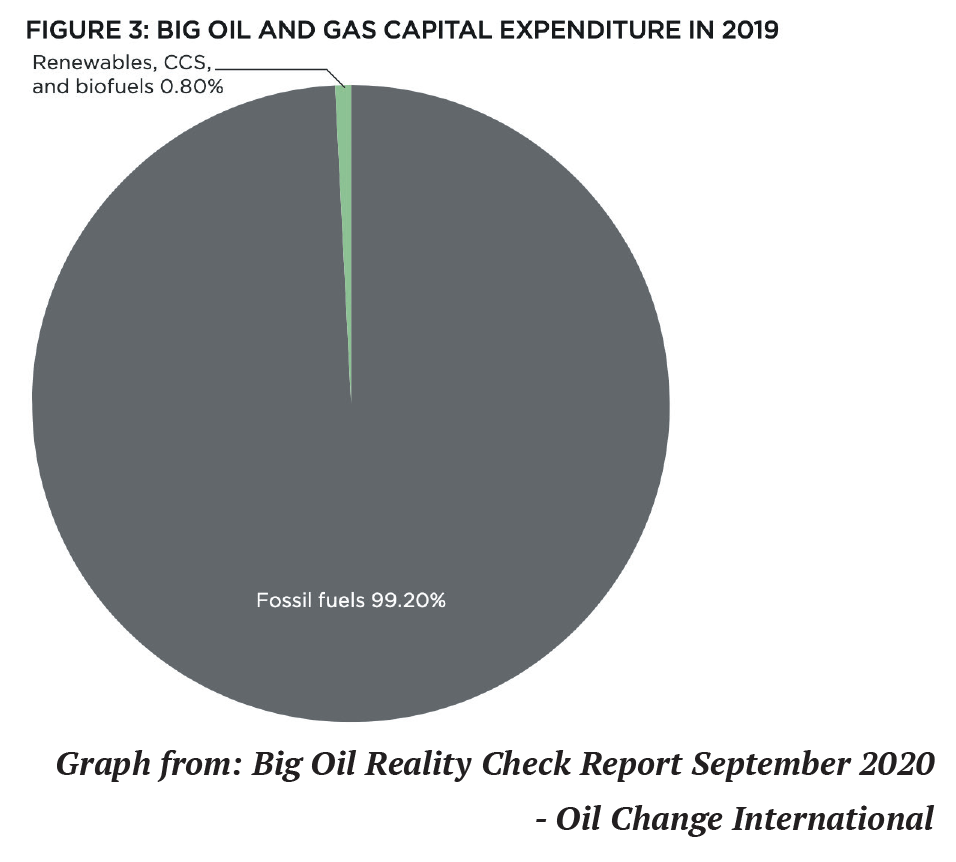

The projects may be beneficial in isolation and contribute to advancing research in sustainable energy, but when viewed in the context of the climate crisis, these small philanthropies are strikingly hypocritical and self- serving (see chart).

WUR, Shell & BP

In a 2017 symposium on Arctic oil and gas hosted by WUR, a former “officer” of Shell was invited and in January 2018, WUR put up a big bright yellow tent on campus to host Shell’s “Bright Ideas Hub”.

In 2015, a WUR bachelor’s student was awarded Shell’s Bachelor Master Prize for €2,500 because Shell “wants to encourage young technical talent to conduct research into technological solutions with a sustainable character”. On top of that, Louise Fresco, current President of WUR’s Executive Board, was jury chair at this competition.

Research collaborations with Shell & BP

Research in collaboration with fossil fuel companies is hidden in many unexpected places at WUR. In 2015, a research project on “marine oil-snow sedimentation and flocculent accumulation (MOSSFA) events during the Deepwater Horizon” was supported in part by a grant from BP. Charitable as this funding may seem, let’s not forget that in 2010, the historic Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico was blamed on BP’s “gross negligence and wilful misconduct”.

Shell appears in many places. A report on the “potential of coproduction of energy, fuels and chemicals from biobased renewable resources” was co-authored by a WUR researcher and an employee from Shell.

Shell is also a party in the consortium in the Aquaconnect programme, which focuses on the reuse of wastewater and brackish water for drought resilience in the Netherlands.

Apart from being a partner in these projects, Shell appears to be a major collaborator in Wageningen’s Institute of Marine Resources and Ecosystem Studies (IMARES). IMARES aims to “substantially contribute to more sustainable and more careful management, use and protection of natural riches in marine, coastal and freshwater areas” and has conducted at least 17 studies in partnership with Shell.

With a track record of environmental damage in marine areas, it seems questionable that Shell would be an appropriate partner in achieving IMARES’ research goals.

Shell is an official partner of the Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Metropolitan Solutions (AMS), which tackles “the challenges posed by our rapidly urbanising world” and was founded in 2014 by WUR, Delft University of Technology and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As a partner in this project, Shell claims to be helping focus on “the research and development of smart and sustainable energy systems”.

Finally, Shell is listed among the partners of WUR’s Dutch Arctic Circle project, which aims to:

“connect supply and demand of Arctic knowledge in the Netherlands in order to work towards responsible offshore operations”.

With the long list of environmental problems that come with fossil fuel extraction, let alone offshore operations, it is questionable that “responsible offshore operations” are possible – and that Shell can be part of this ambiguous goal.

Apart from collaborating with BP and Shell individually, WUR also has a few projects with multiple fossil fuel collaborations.

WUR’s AlgaePARC researches the production of bioplastics, biofuels, and food additives using algae. They partner with the fossil fuel giants ExxonMobil, Total, and Equinor as well as with Neste Oil, SABIC, and Staatsolie Suriname.

One of AlgaePARC’s projects is FUEL4ME which aims to make “second generation biofuels competitive alternatives to fossil fuels.”

SYMBIOSES, short for “system for biology-based assessments”, was a WUR project that ran from 2011 to 2014, using “evidence-based, quantitative analyzes [sic] of the potential impacts of petroleum developments and other activities in spatially managed ecosystems’’.

The aims of the project were to assess the effects of petroleum “activities” on fish and plankton communities. The project’s clients included Equinor and 5 of the 6 Big Oil companies (Shell, Eni, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, and BP).

The aims of both projects may appear unproblematic, but they are prime examples of greenwashing by these fossil fuel companies.

They fund green research to bolster their public image.

The revolving door

There appears to be a revolving door between Shell and WUR, with previous Shell employees ending up at WUR.

For example, a researcher at the Food & Biobased Research Institute of WUR did a traineeship at Shell/ ExxonMobil on drilling fluids before working at WUR. Steven de Bie was an Adjunct Professor in Sustainable Use of Living Resources at WUR after working as Shell’s Manager of Environmental Partnerships and Advisor on biodiversity. He was later made Honorary Professor at WUR (it is unclear whether he still holds this position).

Shell also sponsors Dr Peter Boogaard’s position as Professor of Toxicology at WUR. Finally, Louise Fresco was a trustee of the Shell Foundation for three years up until a year before she was hired by WUR in 2014.

WUR does not take a strong stance against fossil fuel companies, as seen in its ambassador selection. These ambassadors, nominated by WUR, are “a panel of WUR graduates who now occupy important posts in industry and public institutions worldwide”. WUR claims that “each and every one of them are leaders from the business community and the government- related organisations […]. Using their network, experience, and financial resources, [the ambassadors] want to build a bridge between WUR and society.” In 2020, they consisted of 35 Dutch WUR alumni.

One such ambassador is Roelof Platenkamp, who used to work for Shell and on petroleum development in Oman and is founder of Tulip Oil. Tulip Oil is a private fossil fuel exploration and production company, which has a:

“strong portfolio of both onshore and offshore projects in both oil and gas.”

It is troubling to see that WUR chose a prominent businessman in the fossil fuel sector as an ambassador, and even hopes to use his lucrative connections to bridge WUR to “society”.

These personnel ties form a cosy relationship between fossil fuels and the university, bringing the interests of fossil fuels to the centre of WUR. In an ideal world and hopefully the near future, fossil

In an ideal world and hopefully the near future, fuel companies no longer exist. They do not have a place in a world facing a climate crisis – a problem that they are largely responsible for.

Despite their small philanthropies and donations to green research, their businesses still run on the exploitation of natural resources and people, especially people of the Global South and people of colour.

Although we are not living in a utopian world free from fossil fuels yet, we still should avoid these companies as much as possible, and WUR should not have any connections to these companies at all.

There are of course limitations to this vision. For example, what if someone did an internship at Shell and now works at WUR as a post-doc? This should not be our focus; the problem is the system and not the individuals.

The examples of personnel ties mentioned in this article are therefore limited to those that involve decision-making or that enable greenwashing.

WUR’s connections to fossil fuels are unsettling because research is carried out at WUR on climate justice and ethical transitions away from fossil fuels. WUR actively presents itself as the planet’s most sustainable university, and it proudly displays its awards and accolades.

Even WUR’s slogan, “for quality of life”, and its overuse of the colour green, suggest it holds the answers to solving our planetary crises.

But underneath all the glossy sustainability marketing, WUR is still welcoming and accepting the influence of these fossil fuel companies.

In doing so, WUR plays a knowing role in greenwashing and is complicit in a widespread public image scam.

By: Brigitte W.